I stand by what I said that All Lives Matter and that we are human beings.

― Richard Sherman, 2016

#BlackLivesMatter doesn’t mean your life isn’t important if you aren’t black—it means that Black lives, which are seen without value within White supremacy, are important.

― Alicia Garza, 2014

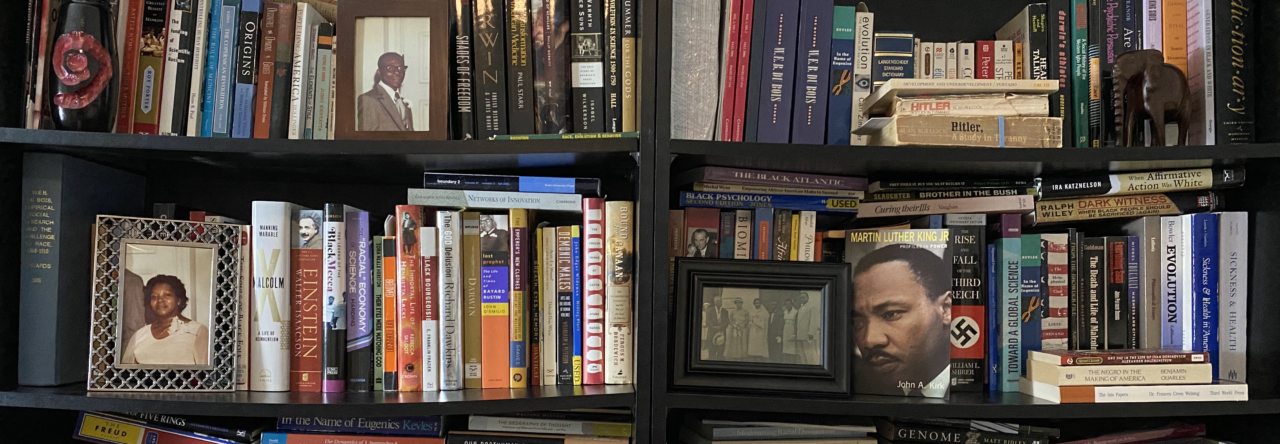

When former Seattle Seahawk Richard Sherman expressed his universal value for human life, doubling down on his point that “All Lives Matter,” I tried to root for him, thinking that I understood where he was coming from. Maybe he was trying to say something profound yet reasonable: that Black people, like everybody else, believe in those elusive principles of freedom, equality and justice. Surely, he was right―if that is what he actually intended to convey. But if he were attempting to argue that all lives matter equally in this country and that we are all treated as free and equal human beings, then, he was flatly wrong.

Maybe, Sherman was confused. Maybe, he was deluding himself. Or, just maybe, he was gaslighting the interviewer. (Regardless, Black Twitter let him have it!)

Without question, I stand with Alicia Garza’s message: that Black Lives Matter. But I go even further. To be frank, the slogan “All Lives Matter” is a dishonest repudiation and rejection of the Black Lives Matter movement. It dismisses observable reality, and it flagrantly disregards history.

The fact is: all lives have never mattered in the United States. This is why Black Lives Matter is especially apropos in this moment. It rings less as a slogan but more as a straightforward appeal: to cease the centuries-old practice of racial terrorism and genocide of Black people. It is, at once, a reaffirmation and a reclamation of Black people’s long-denied humanity.

Intended to awaken the consciousness of a nation, #BlackLivesMatter became a global movement almost immediately after the 2013 acquittal of George Zimmerman in the shooting death of 17-year-old Trayvon Martin. While Martin’s murder was one of an endless spate of white-on-Black homicides over the many, many decades, this February 2012 killing seemed like an outright modern-day lynching, eerily reminiscent of the brutal execution of 14-year-old Emmett Till in 1955. Thus, Martin’s death set off a rage Black America hadn’t felt in more than a half a century.

Rampant, systemic racism continues to kill Blacks. While race relations have experienced its ebbs and flows since the end of the Civil War, institutionalized racism is as strong as ever. Statistically, Blacks face disproportionate disadvantages in all areas of society, from housing to healthcare. Anti-Black sentiment oftentimes manifest in forms of racial terrorism and violence, wreaking havoc on Black bodies. This is a deadly cycle, a reality that has driven the Black Lives Matter movement to bring specific focus to the need for respect and preservation of Black lives, an effort, as Garza once said, “to restore people’s dignity.”

Black Lives Matter is important because the architects of All Lives Matter never considered Black people in their frame of thinking.

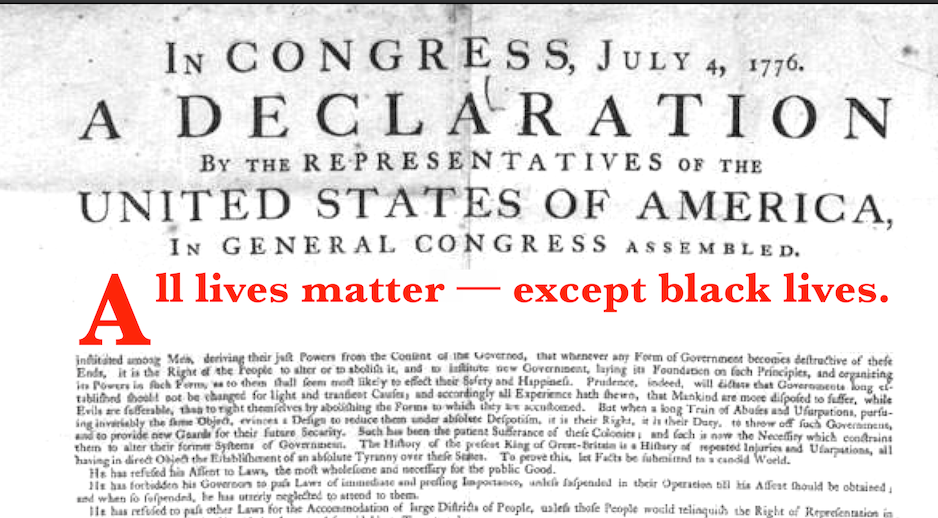

All Lives Matter–A 17th-Century Notion

The modern ideals of All Lives Matter originated in English philosopher John Locke’s Two Treatises of Government, published in 1690, following the Glorious Revolution in England. This was a time in English history when, after nearly a century of absolutist leadership, specifically friction between the monarch and Parliament, constitutional monarchy was restored. In 1689, under the co-regency of William and Mary, the English Bill of Rights was established, and it was proclaimed that the monarchy could not rule without Parliament.

Image: Wikimedia Commons

Charles I was beheaded in 1649 for essentially ruling without Parliament. Locke was 16, and that event left a lasting impression on the teenager: that citizens would rebel if they don’t feel heard. By the time of the Glorious Revolution, Locke was witnessing a renewed role for government: a time when the government’s authority, in theory, would only be justified when the people gave their consent.

Thus, it was the spirit of the Glorious Revolution that would inspire Locke to define many of the enduring ideas of Western political thought. His philosophy ushered in the era of modern democracy.

Locke proclaimed:

The state of nature is also a state of equality. No one has more power or authority than another. Since creatures of the same species and rank have the same advantages and the use of the same skills, they should be equal….The state of nature…teaches that all mankind…are equal and independent, no one ought to harm another in his life, health, liberty, or possessions.

Locke’s sentiment should be familiar to us all because his reflections later formed the basis for the eighteenth-century European Enlightenment: the Age of Reason. His ideals gave rise to the American Revolution and influenced Thomas Jefferson’s famous passage in the 1776 Declaration of Independence: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness.”

Jefferson drew directly from Locke, promulgating America’s most cherished ideals: liberty, equality and justice. Without a doubt, these Enlightenment ideals laid the groundwork for the slogan All Lives Matter.

However, neither Locke nor Jefferson actually believed that all lives mattered, a persistent irony of their legacies. In the late seventeenth century, English power was vested in a Parliament that represented the upper classes, not common citizens. Given the context in which Locke lived and wrote, many scholars have called into question whether he himself was really the forward-thinking idealist his words would suggest. In his article “John Locke Against Freedom,” John Quiggin writes: “Given his reputation as a defender of property rights and personal freedom, Locke has been accused of hypocrisy for his role in promoting and benefiting from slavery and the expropriation of indigenous populations, actions that would seem to contradict his philosophical position.”

Given Jefferson’s station as both landholder and owner of enslaved persons, we can assume that, for him, “men,” in the famous phrase “all men are created equal,” was meant for white male property owners alone. Jefferson, himself a member of the established southern gentry, owned more than 600 enslaved African-Americans over the course of his lifetime. Astonishingly, when drafting the Declaration, the Virginia planter advocated for the abolition of slavery. In fact, in the original document, Jefferson indicted slavery as “a cruel war against human nature itself” that violated the “most sacred rights of life and liberty.” The anti-slavery passage of the draft was stricken. Years later, Jefferson blamed the removal of the passage on contrarian delegates to the Second Continental Congress.

But was Jefferson really concerned about Black freedom?

What prompted the American Revolution was white colonists’ protest against their own metaphorical “enslavement” to the British crown. For White settlers, direct taxation on the Colonies felt like slavery. Whites protested that colonial life was intolerable under the “tyranny” of King George III. So, white colonists staged the Revolution to end their said enslavement. As the story goes, they would fight valiantly for their independence and won their liberty. Yet, the whole while, most Black people were held in permanent bondage.

Thus, after the Revolution, the heralded ideal of “all men are created equal… endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable Rights”—the prime sentiments of All Lives Matter—was proved to be a matter exclusively for white people, particularly white males with property.

Black people, on the other hand, whether enslaved or free, were seen as property and denied the right to human identity. Blacks were considered chattel of the new Republic, not human beings. (The Constitution fortified this dehumanization with the Three-Fifths Compromise.) At the time, the United States remained heavily involved in the Trans-Atlantic slave trade. Slavery, widespread and highly profitable, gave primacy to the economic imperative; morality be damned! As a consequence, the economic dependency on slave labor steadily and sharply expanded, from roughly 300,000 slaves in 1790 to approximately four million in 1860, just before the Civil War.

So, when exactly did Black lives matter?

Black Lives Matter–A Movement for All

Since 1619, long before Locke, Black people had embraced the ideals of All Lives Matter: liberty, equality and justice. It would be the key aims of the abolitionist movement in America.

Beginning with Crispus Attucks, who was thought to be the first casualty of the American Revolution, Black people had fought in every American war, believing that their valor, loyalty and sacrifice would gain them freedom. Black people have died for the aspiration of freedom, equality and justice―for all―willingly and unwaveringly. Thousands of Black Patriots fought during the American Revolution. Nearly 179,000 Black people fought for the Union Army during the Civil War. Some 40,000 Black soldiers lost their lives in that war.

The New York Historical Society

After President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation in 1862, Frederick Douglass, a progenitor of the Black Lives Matter sentiment, reflected on the potential impact of freedom on all Americans: “Everybody is liberated. The white man is liberated, the black man is liberated, the brave men now fighting the battles of their country against rebels and traitors are now liberated… I congratulate you upon this amazing change—the amazing approximation toward the sacred truth of human liberty.”

Yet, Lincoln’s proclamation, which did not free one slave, was more political ruse and military strategy: a way to change the tenor of the war, from being about saving the union to freeing the slaves. It was not a proclamation that Black lives mattered. The Union desperately wanted to win the war; it needed a cause for which Black soldiers would also fight and die. Blacks helped, in fact, deliver a Union victory.

After the Civil War, Black citizens also actively committed themselves to participating in Reconstruction, demonstrating their faithful belief in the tenets of the Republic and the necessity of repairing a fractured country and restoring a devastated South. Yet, following the Federal abandonment of Reconstruction in 1877, Black Americans were subjected to a century’s worth of legal apartheid under Black Codes and Jim Crow and de facto repression. Generations of Black people endured state-sanctioned terrorism and violence as a normalized way of life.

Still living under both the promise of equality and the ominous cloud of a racial apartheid, Black Americans continue to plead for their inalienable rights and their humanity to be acknowledged and protected.

In the wake of the George Floyd murder and the subsequent global protests in defense of Black lives, Richard Sherman, now a San Francisco 49er, has changed his tune. He has come to a realization that, #BlackLivesMatter cannot be “a fad and fleeting” phenomenon. He is right. Black lives cannot be overlooked or neglected. They must matter today, and “[t]hey have to matter forever.”

Black Lives Matter is an inclusive proposition that clings mightily to Locke’s basic fundamental tenet: that the role of government is to protect the natural rights and freedoms of its citizens. If history is our guide, Black Lives Matter is a matter of liberty or death.

Carlton edwards

I saw it earlier on FB. You know this is a thought one for us as a whole because black people do believe that all lives matter. The problem is because of the treatment of us as blacks by the rest of society causes the statement to be worst than the N word. BLM is at this point all that matters to us as black people. Until we are served a equal slice of the pie our platform can only be used to say BLM. I do believe in BLM because in the end this is all we have that is a 💯% ours no matter who helps us along the way.