My Students’ Call to Action

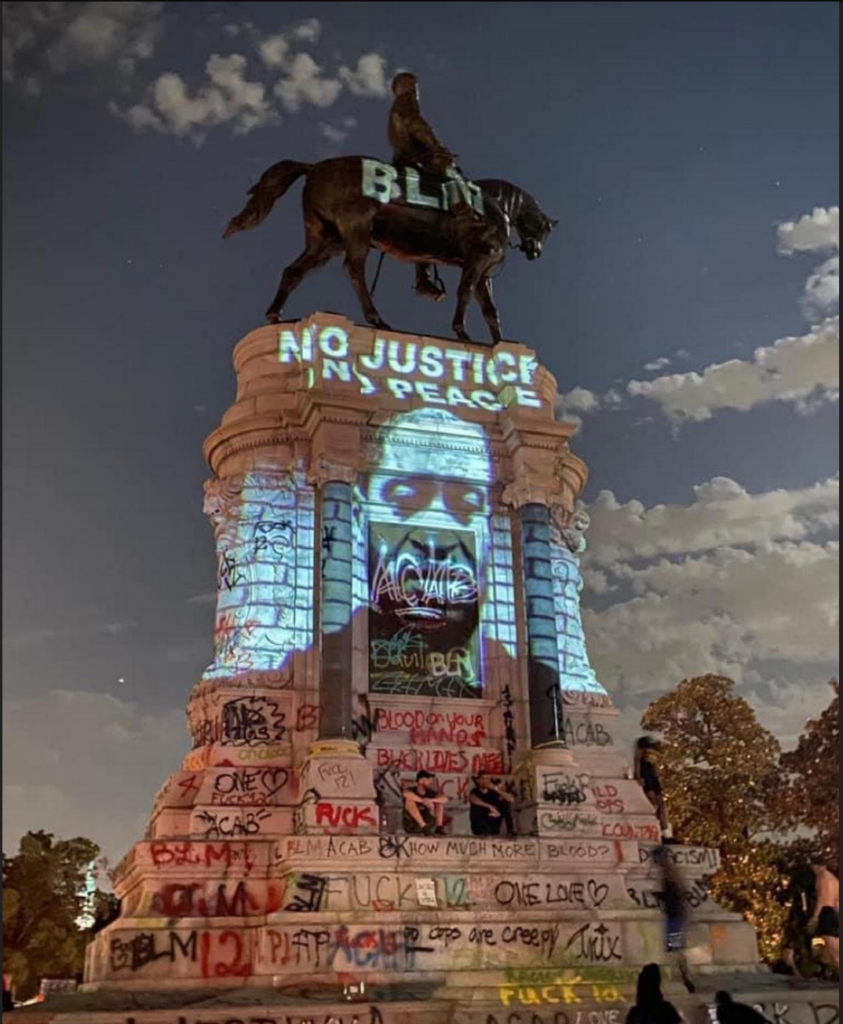

(Credit: Reddit, Alexis Delilah)

“I like history, but sometimes I feel like you could be more concrete as a teacher—like, just tell us the facts, just what happened,” complained a young Black student in my world history class.

“If history were concrete, history would only show us in chains. History should be about constantly breaking down and pulverizing the ‘concrete,’ so that we actually exist—in our fuller truth,” I responded.

______

Over the years, I have thoroughly enjoyed teaching history, but I spend a great deal of my time being frustrated. It is disheartening when students just merely want to be told stories or the so-called “facts” (which are oftentimes widely accepted myths). This is not history.

At the beginning of every school year, I find myself spending the first two weeks de-mystifying my field of study, championing its greater cause as part of something larger, more dynamic. Over and over, I say to my students that history is supposed to make you think. It is supposed to force you to ask more questions. It is supposed to make you want to raise hell, to do something.

I am not the conventional history teacher. If my classroom were anything like Romper Room, merely fun and games, memorization and regurgitation, symbols and slogans, I’d quit and do something else. Instead, the classroom, in my view, is a place where action happens. I myself see teaching as a form of activism that produces critical thinkers. Activism means learning in order to effect social and political change. Thus, thinking is activism.

Finally, today, I am seeing the fruits of my labor—out there in the streets.

In the midst of this global pandemic, there is a restless hankering for change. At once, we are fighting two pandemics: COVID-19 and systemic racism. Young people are questioning; they are demanding and doing so unapologetically. The country has reached an inflection point, and young people are tearing shit up, forcing us to craft a new narrative, not only of the past, but one of a more inclusive future.

I am reminded constantly of a statement my late father said many times in my childhood. “In order to stop racism, the whole of this generation muss die out—completely.” As a young child, I believed my father. As a young adult, I stopped believing his words. As a middle-aged educator, I am hopeful.

In the wake of the George Floyd lynching (let’s call it for what is actually was), I find myself conceding to the young people who are demanding change. I have retreated to a place of quiet, in a seemingly endless moment of reflection, in a mood angry, enraged, yet eerily calm.

Many of my colleagues of my generation who grew up in the 1970s and came of age in the 80s were told that knowledge is power, and that it could change the world—we hoped. A good swath of us became professors and teachers. I have been both. Today, my generation is middle-aged—still working, still teaching.

Our young protégés are, too, educated, armed with the history and knowledge of this country, fully loaded with a vision for change. Perhaps, finally, they can help us write one final chapter: the end of the Confederacy, once and for all, because the Confederacy has not lost, yet.

I call this period a reset in the course of American history, and I suspect that many of my former students are responsible for this. I, too, take some credit, because since 1994, I have taught thousands of young people. My youngest students were all born after 9/11, and they are angry. They have grown up without knowing privacy (because of the Patriot Act and social media); they have seen this particular administration fleece the country and cheat them out of a more certain future. They have witnessed lynchings real-time on Facebook Live, Twitter and Instagram. They are young and energetic. And they have had enough—of the lies.

These times certainly demonstrate that students do grow up and use what they have learned in the classroom as a form of activism. This is the moment many of us have waited for: when the mythology of white supremacy would finally meet its match: Raised Consciousness.

A couple of weeks ago, young citizens spray-painted various words in multiple colors all over the Robert E. Lee statue in Richmond: Fuck 12. ACAB. BLM. Pigs. Amerikkka. Columbus’ statue was beheaded in Boston. In Baltimore, they bum-rushed Columbus; his white, concrete body was toppled—and then thrown into the harbor. In Houston, folks gave Columbus’ entire face a drenching of blood-red paint.

In the wake of another murder—just blocks away from my Atlanta home—I visited the site where Rayshard Brooks was gunned down by a white police officer in the parking lot of a Wendy’s. I took pictures of what looked like a burnt and gutted fast-food grave. All that remained was the structure. But it was spray-painted quite colorfully with multiple messages in pink, red, black, green, gold: “Fuck 12,” “Bigger Than Blk N WHT,” “Rayshard.” I found myself hoping the city would leave this structure alone, as is, to the community—to history. It tells the story of this moment, better than any statue.

America is comfortable with the myth of itself: that it is the land of the free, home of the brave.

Challenging this myth can be exhausting, but it is the work of decades of breaking the proverbial concrete of mythologies. It is why there was a movement over the decades to bring about Black Studies, Chicano Studies, Queer Studies, Gender and Women’s Studies, etc.

In the midst of it all, a close friend called me, miffed and perplexed that he has, in his circle, a white friend who actually believes that the Confederate monuments and the Confederate flag are symbols of Southern “heritage,” reminders of Southern history—not of racism.

“Perhaps you should ask your friend to define ‘heritage,’” I said. “Heritage is not a synonym for history. Veneration of a violent and racist past—like, celebrating the Civil War—is more like a continuation of racial terrorism.” But, I argue, if the Confederacy had actually lost, we wouldn’t be having these debates, still, 155 years later.

The South won the narrative, and the right to lay claim to an active racism, one that both the North and the South would endorse for the next century and more. This gave rise to a legal and cultural apartheid that would become the familiar air of Americana, allowing white supremacy to reign supreme in both the North and the South. In 1969, when my Jamaican mother, with her friend, ignorantly sat at a lunch counter in a suburban Maryland diner, “every white person stopped eating and looked ‘pan we, and we felt shame,” my mother recalled. Over the years, she re-told this story many times, and I got it: that white supremacy was in full swing, even in the border states, too—not just the South.

So, it is not lost on me that the South’s putative loss really became a “moral” victory at the expense of Black freedom and Black lives the country over. This is why I continue to argue that the Confederacy still lives—infamously.

A few years ago, one of my tenth-grade students came up to me after a lecture and asked why I wasn’t speaking to a larger audience instead of just a classroom of kids. I felt like he was either complimenting me or taking a dig. I felt honored and guilty at the same time—because it seemed like he was asking why I wasn’t doing something bigger. He added that folks needed to hear what I was saying, to know the “stuff you are teaching—the way you see the world.” After reflecting on what the student had said, I took his statement as a compliment and thanked him.

Will I go back to the classroom this fall—in the middle of this dual-pandemic? Yes.

History is where we have the power to reset things. The perfect friction between art and science, reason and emotion, it is an act akin to nation-building. Caroline Randall Williams makes the point brilliantly in her New York Times op-ed piece, “You Want a Confederate Monument? My Body Is a Confederate Monument.” History is an ongoing project, of sorts, and we must “understand the difference between rewriting and reframing the past… not a matter of ‘airbrushing’ history, but of adding a new perspective.” My students are doing just that!

This upcoming Fall, more than any other time in my career, I will try to eliminate the line between the classroom and the real world. The cocoon of the classroom will continue to be a place of dialogue and debate where big ideas happen, where we explore and critique the world—on terms we imagine and create. It will be a huge undertaking. In this respect, I pledge that my classroom will never, ever become Romper Room. It will be fun, of course, sometimes even exhilarating. But also, sometimes scary. Potentially unnerving. But real shit. And students will get it. My former students out there protesting for change have gotten it. That, to me, is big.

When my students are done, the Confederacy will have finally lost the war!

Carlton edwards

Good read, keep their minds thirsty and fill it with the knowledge of real change.

odete

Great read. Wonderful that someone like you is helping to ‘shape the minds” of future generations.

Roxie Hughes

Great post. Although I appreciate your hopeful message, I wonder if your perspective would be the same if you taught at a public school in one of the northern counties in GA? That’s where a lot of my white coworkers live and for the most part, they are ultra-conservative, bible-thumping Republicans. They would be the first to lament how those confederate monuments are a part of their ‘southern heritage.’ So as much as I would like to believe their children might rebel against that brainwashing, I have to admit that I’m a bit cynical. But hopefully, your students will beat down my coworkers’ kids with their passion even if they are outnumbered. Keep up the great work!!

John H Davis

Thank you so much for this–it was truly moving.

Inez McDowell

I enjoy reading your stories, thank you for broadening my knowledge.

Roxie Hughes

Also, I totally agree with your student who suggested that you should be sharing your knowledge with a larger audience. The world needs to have the benefit of hearing your history lectures. So with that in mind, I would like to posit that you should create a YouTube channel and post short videos where you discuss historical topics that are relevant today. For example, a video explaining the historical context of when these confederate monuments were erected would help level-set the discussion/debate about whether they should be taken down. 👍🏽

Emily

Thank you for articulating what we try to do as history educators.

Sharon Arrington

Thanks for enlightening our young people, great job. Keep grooming thinkers instead of testers.

ปั้มไลค์

Like!! I blog quite often and I genuinely thank you for your information. The article has truly peaked my interest.